This article was originally published on American Conservative. You can read the original article HERE

Everyone has the occasional bad class, but my worst run of sustained teaching failure came during the fall semester of my first year. I do not include the spring semester because the class in question consisted of twelfth graders, and end-of-year exams, graduation ceremonies, and my own tacit surrender ended any pretense that I was actually teaching those students by some time in February.

People curious about school assume that the bad classes are filled with spitball-launching hard cases. This is surely true for some unlucky teachers, but my worst classes were always the apathetic ones. I had just enrolled in what I thought would be a one year stint in a teaching program for Americans in Central Europe. I ended up in a village in Northeastern Hungary.

Teenagers today are sadder and more anxious than a generation ago. The surgeon general has declared a youth mental health crisis, depression and related psychological problems are on the rise, and minor key, down tempo songs about loneliness and isolation have displaced anthems and ballads on modern pop charts. Covid is the obvious explanation, but most of these trends preceded the lockdown era, which suggests that draconian public health measures were an accelerant and not a root cause. Quarantine merely worsened a suite of preexisting problems.

The twelfth graders who defeated me were enrolled in the school’s B track, which meant they took easier classes than the more academically gifted A track students. One cultural difference between Hungarians and Americans is the former’s often disconcerting penchant for directness. A Hungarian homeroom teacher once told me, with no preamble, that her class was nice but not very clever. Everyone said the B students weren’t interested in or good at schoolwork. There were a few notable exceptions, but this judgment usually proved to be correct.

Various reasons have been suggested for the recent rise in teen anxiety, some plausible, some less so. I do not think that 15-year-olds are naturally preoccupied with climate change, for example. I doubt that bullying, cliquishness, and other behaviors that have made adolescents miserable since time immemorial have suddenly become worse. So, what’s changed?

I often think back to that 12B group, probably because the things I could have done better are trivially obvious in hindsight. During the pandemic, several states waived teacher training and licensing requirements to address urgent staff shortages. These measures had no impact on instructor quality or classroom outcomes, which tracks with my experience. There is no substitute to being in a classroom, screwing up, and resolving to do better next time. Those interminable sessions with 12B were the tribute I paid to succeed in future classes. Cold comfort to my earliest students, perhaps, but true nevertheless.

There is one obvious culprit for the adolescent misery crisis. Psychologists have observed that rising teen sadness roughly coincides with the introduction of smartphones and the rise of social media. You might call this a moral panic. But wouldn’t it be strange if near unlimited access to the greatest repository of distraction in human history, combined with social media networks that prey on our every vice and insecurity, didn’t change young people’s behavior?

As classes advance through high school, they acquire reputations in the staff room. Sympathetic Hungarian colleagues assured me that 12B had always been a “difficult” group. It didn’t help that I couldn’t speak their language, had parachuted in a year before graduation, and was teaching a subject that, while useful, wasn’t strictly necessary for their post-high school careers. It’s not hard to teach the bright, enthusiastic kids. Learning how to deal with students who struggle academically is the real challenge. The most heartbreaking cases desperately want to learn English but stumble over the simplest phrases. Their more gifted peers effortlessly acquire the vocabulary and conversational tics of a suburban American teenager by watching Youtube.

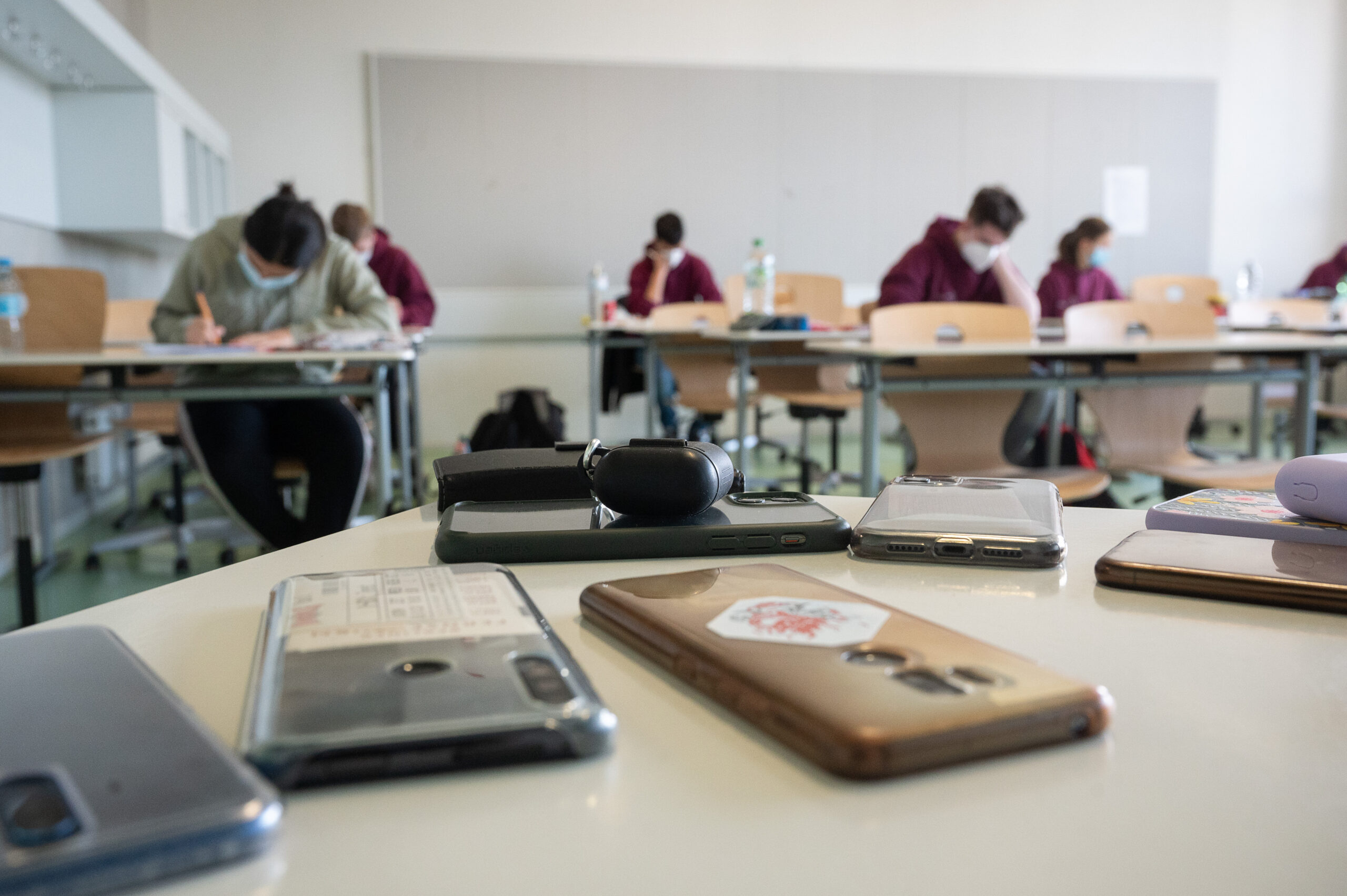

Quite by accident, I witnessed the smartphone revolution progress in observable increments. When I started in the countryside, smartphones were common, but they were sufficiently expensive to be shared among families or siblings and were usually not given to younger kids. Limited data plans and the absence of an open school wifi network, something the students regularly complained about but which in retrospect seems a blessing, also curtailed phone use in school. So did a certain old-school Hungarian mentality about classroom behavior. When I moved to a private school in Budapest, students were granted unlimited wifi access and had been using smartphones since elementary school.

I gradually got better at teaching the B groups. Looking back, many of my favorite students were from those classes. Am I protesting a bit too much? Maybe so, but the B students were more likely to play pickup basketball, more patient with my halting attempts to speak Hungarian, and sillier than their more sober-minded counterparts in a charming, unselfconscious way. Sometimes you forget that academic talent is not the sum total of a student’s life.

Private school was still fun. I could no longer bask in the virtue of teaching “normal” kids, but there were certain compensations: unlimited printer access, frequent field trips, not having to reserve one of the three rooms with a working projector a week in advance. The students were sharp and typically entered high school with an impressive command of English, thanks to private tutors, English-speaking parents, international vacations, and life in an increasingly cosmopolitan Budapest. It can be very rewarding to help a struggling kid master the basics of ordering a hamburger, but it’s also a relief to skip the preliminaries. Something was a bit off, however. Attention spans were shorter. Policing phone use in class was a constant issue. The pandemic didn’t help matters.

A 9B group I was particularly fond of once played a trick on me straight out of Tom Sawyer. It was the first day of glorious spring weather, and the students wanted to hold class outside, something you can get away with when you teach in a village. We went out to the school playground but 9B insisted on going to another park because, they explained, they didn’t want to be bothered by the younger kids at recess. As soon as we were out of sight of school, half of them produced cigarettes and lit up. All I could do was laugh.

Smartphones and social networks are almost certainly useful for picking up conversational English. The barrage of memes, video clips, and English media has endowed smart, language-savvy kids with a level of fluency their predecessors could only dream of. A few older teachers clearly resented this. Imagine learning English the old-fashioned way in 1980s Hungary, through copious note-taking, endless grammar exercises, and rote memorization. Then some snot-nosed 14-year-old shows up on the first day of class already sounding like a native speaker.

There were other classroom screwups. An enthusiastic middle schooler with a shaky grasp of history turned what was supposed to be a Greek hoplite shield into a surrealist work of art. Another student, playing the role of an aggrieved witness during a mock trial, burst into tears during cross examination. I rushed to her side, certain I would be fired for excavating some long-buried trauma for the sake of a dumb speaking activity, only to learn that she was just very committed to the role. A Studs Terkel-esque figure should travel the world interviewing ESL teachers and record their classroom war stories for posterity.

The obvious issue with smartphones is that they diminish students’ attention spans. A less remarked upon problem, one that I realized only gradually, is that they sap young people’s curiosity. The Internet was supposed to inaugurate a golden age of information access. You can take entire classes from Yale and MIT online, free of charge. It turns out that access without guidance is worse than useless. The very availability of information discourages students from picking up a book because whatever they’re looking for is a Google search away, or so they think. Immersion, memorization, even note-taking are considered relics of the bad old days. Paradoxically, those with a preexisting store of knowledge are best positioned to navigate the torrent of information online, like the proverbial boomer with a healthy relationship to social media because he already enjoys a rich offline life. Young people who grew up in this baffling information landscape are the least equipped to handle it.

I remember a comment from a self-described prep school teacher under a New York Times article on education. We have such fun in class reading Shakespeare and Chaucer, he wrote, and then all my students go off to college and end up at McKinsey or Goldman Sachs. Why teach if your take-home pay isn’t even in the same universe as other career options? My man, you get to make a living introducing Shakespeare and Chaucer to young people. The pay stinks, but there are other compensations.

One seemingly trivial example of how technology can be actively harmful in the classroom has to do with note-taking. Nobody likes taking notes, but the act of writing something down is a potent mnemonic device. Uploading your slideshow and allowing students to take photos of the board seem like obvious time-saving measures, but this makes it harder for them to remember things and leaves kids with nothing to do during lectures (idle hands are the devil’s playthings). You can take notes on a laptop, of course, but it is trivially easy for students to pretend to type while they do something else. Instead of improving the classroom experience, technologies everyone assumed would be a boon for teaching have needlessly complicated a tried-and-true method of instruction.

I’m not sure when it happened, exactly, but the first short story I ever taught was “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” It did not go well. I was desperate to fill a 45 minute class with something, anything, so I dug up a story I vaguely remembered enjoying from middle school. The first half did take up every second of that period. As if by some unspoken accord, the students and I did not return to or even mention Mitty the next lesson. I’ve gone back to that story every year since.

My fear is that the advance of technology in schools is seen as an inevitability and not something to be managed and, in certain cases, curtailed. There is an understandable desire on the part of principals and administrators to stay on the cutting edge of new developments, or at least sufficiently up-to-date to stay relevant for tech savvy students. I am not such a luddite that I wish to ban computer science classes. But the relentless colonization of every subject by laptops, “interactive” digital tasks, and other distraction-inducing measures have done more harm than good.

I like listening to my students read out loud. The Hollywood stereotype of a harsh Eastern European accent comes from the Slavic languages, which do not mix well with English. Hungarian, however, is not a Slavic tongue. It has its own sing-song quality that makes it enjoyable to listen to, even when the speaker is an increasingly agitated lady explaining that, no, you can’t pay with your debit card in this particular checkout line. When combined with the British style of instruction that still predominates in Hungary, it produces a charming, musical English accent.

Covid school closings show just how hard it is to roll back technological “advances.” Everyone knows that remote instruction was a disaster. Yet schools continue to hold online classes for all manner of disruptions, from snow days to flu outbreaks to the sudden arrival of busloads of illegal immigrants. Who asked for this, aside from bureaucrats who get to say that they haven't lost any teaching days to inclement weather?

We were reading “The Necklace” by Guy de Maupassant, one of those classic short stories that has survived countless curriculum changes, and I was trying to explain the concept of “theme.” Class, can you think of any other books or films with a powerful thematic message? From the back of the classroom, a hand is tentatively raised. “I think I have an idea, Mr. Collins.” (pronounced Koll-leenz) Thrilled that someone from an often uncommunicative group has volunteered an example, I respond enthusiastically. What have you got for me, kid? “I was thinking about the importance of family. You know, from the Fast and Furious movies.”

The (thoroughly debunked) idea that students have different learning styles is a staple of teacher training programs. Maybe this is because teachers are stupid. A more charitable, and to my mind more persuasive, explanation is that teachers want to find ways around the seemingly intractable problem of kids’ vastly different academic abilities, an uncomfortable reality that is apparent to anyone who spends time in a classroom. It’s easier to tell yourself that adding a few “kinesthetic” or “auditory” exercises to a lesson will help slow learners than facing up to the fact that some of your students just aren’t very good at school. Technological fads are a more expensive way of evading that same awkward truth.

I remember when the village school received a stack of tablets for classroom activities. They ended up collecting dust in a storage closet. This was a school where kids had to bring in their own toilet paper. Nobody gets excited about grants for bulk toilet paper purchases, however.

Sal Khan, of Khan Academy fame, wants to give every kid who needs tutoring an AI-powered chatbot. There is a short science fiction story from Isaac Asimov, “The Fun They Had,” that centers around kids taught by robots. They discover an old book and are astonished to learn that schools once had human teachers. I’ve never taught this story because I always assumed the premise was too absurd to contemplate.

Rote memorization is underrated. There, I said it. Older teenagers aren’t going to get excited about reciting a poem or a passage from Shakespeare, but you’d be surprised how quickly younger kids take to memorization. It’s a bit of a challenge, they get to perform in front of their classmates, and there’s a rhythmic, incantatory quality to many older verses. Kipling and Macaulay are great for this sort of thing. I also like to think that some students are “poetic” learners. Maybe they can add that to the learning styles canon.

“Educators tout it as the perfect tool for teaching the TV generation — a technology that weds television, compact discs and personal computers into something called interactive video.” That was The South Florida Sun Sentinel on laser discs, November 12, 1991.

It’s possible that fears of classroom technology are overblown for the same reason that different learning styles are nonsense; strong students will succeed and weak students will struggle regardless of circumstances. I don’t believe this is true—good teaching can make a difference and, even if you’re not raising anyone’s IQ, young people benefit from exposure to serious ideas. There is a more fundamental problem, however. Just as the Internet, a tool that promises unlimited information, can actually discourage curiosity, smartphones and social media paradoxically undermine the social relationships they’re built on. These products seem purpose built to frustrate adults and make adolescents miserable.

“Online feels more peaceful and calming,” Nate, age 14, tells the New York Times. “You don’t have to talk to anybody in person or do anything in person. You’re just sitting on your bed or chair, watching or doing something.”

The default position of a young person today with a few minutes of free time between classes is hunched, in a pose reminiscent of Rodin’s “Thinker” minus the pensive stare, over a flickering screen. Students spend less time interacting with classmates and teachers and more time consumed by their devices. There are two dominant modes on social media: relentless affirmation or content that preys on your every anxiety and insecurity. Neither is particularly healthy for young people. There is also the constant temptation to withdraw from real world uncertainty into a reassuring virtual cocoon designed to keep you hooked. Why date, play a sport, or hang out with friends when you can retreat to a carefully manicured digital environment?

Concerns about smartphones and social media transcend ideology or partisanship. The youth culture celebrated by the left has been sapped of its vitality; Nirvana and Rolling Stones t-shirts easily outstrip merch from any contemporary musician. Teenagers, long assumed to be eager rule breakers and instinctive rebels, now ape the styles of prior generations without any of the accompanying experimentation or energy. Cultural vitality is not the only casualty of this new landscape. The decline of dating threatens family formation and healthy adult romantic relationships. Alienation and loneliness threaten the very fabric of society.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

I no longer teach high schoolers. Everyone assumes I’m thrilled to have “graduated” to university classes. It’s true that I’m now less likely to lose my temper or get stuck in an interminable meeting. I still miss the younger kids. I don’t mean to romanticize high school, which is often awkward and sometimes much worse. But it is a vital stage in a young person’s social and intellectual development, and it’s perverse that we’ve so readily acquiesced to an unprecedented change in how teenagers encounter the world. Take it from someone who has airballed his fair share of lessons—you always regret just giving up.

One unsatisfying thing about long essays on pressing social issues is that they usually offer little in the way of practical solutions. Well, I have a straightforward proposal that will not “fix” education, but will at least diminish the tidal wave of anxiety and distraction affecting young people. Ban phones in school. Don’t leave it to individual departments or teachers who need predictability and administrative cover for enforcement. Don’t make phone bans the sole preserve of boarding schools, elite public schools, and other affluent enclaves. Teach computer science, teach kids how to code, but spare the rest of our classes the scourge of the smartphone.

There is one poem I’ve taught with a 100 percent hit rate. I usually save it for my final class of the year. We talk about the story of Odysseus and what it means to have a “hungry heart.” The last verse of Tennyson’s “Ulysses” is best listened to with your eyes closed. The language is archaic and almost impenetrable, especially for non-native speakers. Somehow it still hits, even in a musty, uncomfortably warm classroom at the end of eighth period. After you leave high school, dear students, will your hearts stay hungry? Will you continue to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield? We can only hope.

This article was originally published by American Conservative. We only curate news from sources that align with the core values of our intended conservative audience. If you like the news you read here we encourage you to utilize the original sources for even more great news and opinions you can trust!

Comments