In history, as in life, we often don’t appreciate things till after they’re gone. When it was around, we took it for granted — maybe even made fun of it — and so we are caught at a loss when it goes away.

This was the story, for example, of the American West. In the 19th century, when the West was actually being won, it was not a subject of popular fascination. There were, after all, other things going on in the U.S.— such as the Civil War.

But then, in 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner published The Significance of the Frontier in American History. Noting the U.S. Census Bureau had declared the frontier closed, Turner predicted that public fascination with Cowboys and Indians and all the rest would spike up—and it did. Annie Oakley and other Wild West shows enthralled city folk with tales from bygone days of shootin’, ridin’, and cowpokin’.

We are reminded: Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

So now to D-Day, 80 years after. The achievements of the men who stormed the beaches at Normandy speak for themselves. Thanks to them—and to others on other fronts, including in the air and on the sea—Hitler was defeated, Europe liberated, and the Holocaust ended.

Yet only recently has D-Day become a days-long extravaganza of heads of state, flyovers, parades, and pageants. And at the heart of it all, of course, the wizened few men that remain.

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of D-Day at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France, Thursday, June 6, 2019. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus)

As an aside, not all of the vets in France today are actually D-Day veterans, but that’s okay—anyone who wore the uniform, or worked in war production, has a right to say, “I did my bit,” and to be rightly honored. (In 2017 Breitbart News devoted a richly detailed article to the memories of those whose ancestors had worked at the B-24 Liberator plant at Willow Run, Michigan.)

But of course, as any war vet, or anyone who has seen Saving Private Ryan—especially that harrowing opening scene—knows, deadly combat is the ultimate test, and for many, the final and complete glory.

So now today, the memorialization—and the celebration—in France. Said one eyewitness of an event on June 5,

This has to be the longest standing ovation for anyone or anything I have ever witnessed. 4000 high school students in Normandy, France standing to honor our World War II veterans. This area in northern France has not forgotten the events of 80 years ago.

To which we can only say: Good.

This Baby Boomer can remember when, in the eye of the media and the popular culture, D-Day and the Good War seemed like no big deal.

After the war ended, in the late 1940s, GIs were rushing to get back to normal, aching to put the war behind them. When they got home, they were welcomed as heroes, but they were also confronted with broken marriages, lost jobs and derailed careers, drinking problems, and what we would now call PTSD.

These ills were captured in many media, including the 1947 book Back Home, by Bill Mauldin. Himself a WWII vet, Mauldin carved out a career for himself as a cartoonist. As he chronicled, some of those heroes were, in fact, sleeping on park benches when they got stateside.

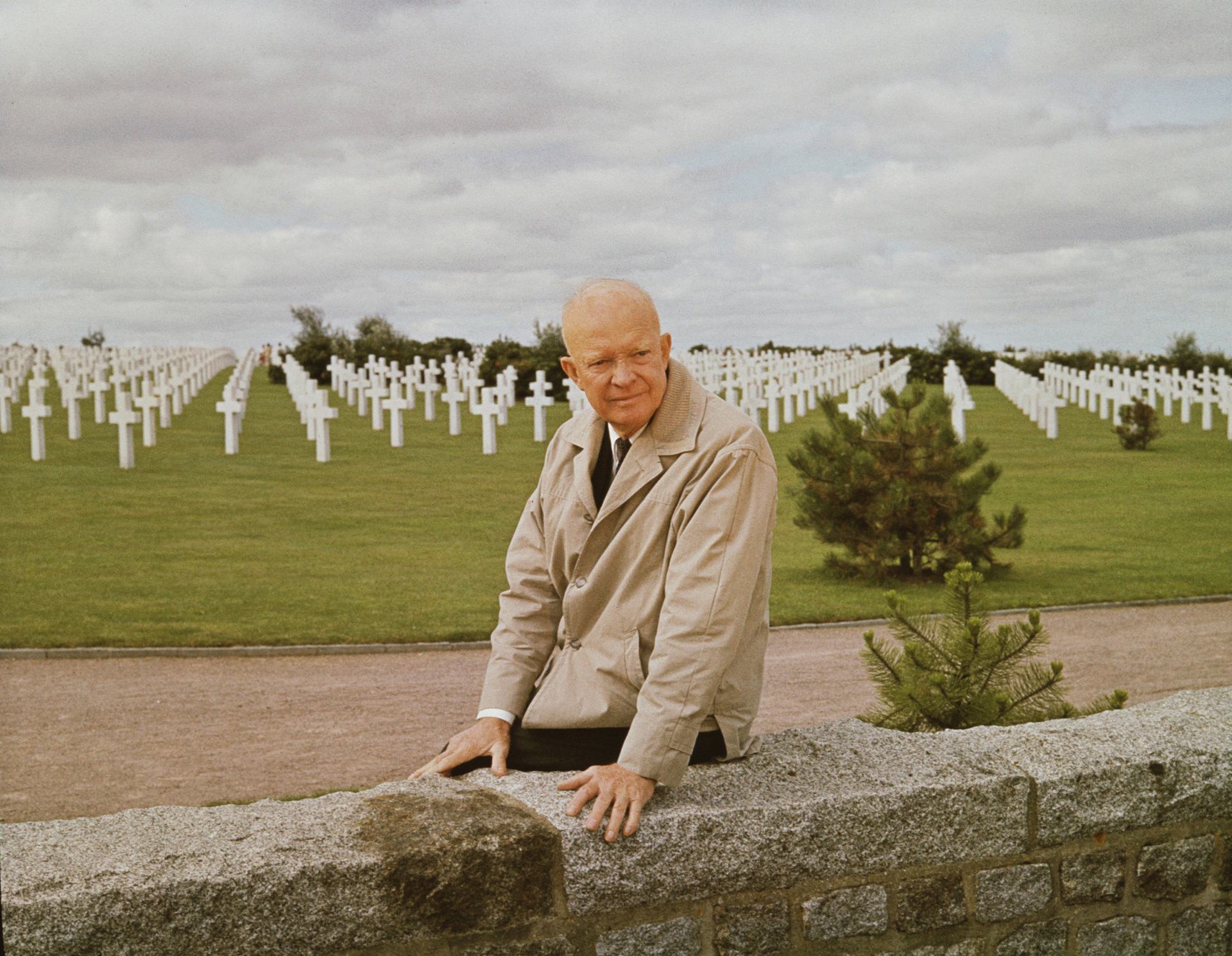

In the 1950s, memories of the war were fresh, and yet virtually all of the 16.4 million veterans of the war were still alive, representing some ten percent of the population of the country. So paradoxically, there wasn’t so much discussion of the war, because everyone knew about it. Yes, Dwight Eisenhower, the supreme commander in Europe, was elected president in 1952, and yet in the White House, Ike seemed more like an uncle or a grandfather than a five-star.

Former American President and military commander Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890 – 1969), with American journalist Walter Cronkite (not pictured), revisits Omaha Beach and other actual sites and locales connected with the World War II invasion during an episode of ‘CBS Reports’ called ‘D-Day Plus 20 Years: Eisenhower Returns to Normandy,’ France, April 3, 1964. (Photo by CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images)

In the 1960s, perceptions of WWII were colored by the unpopular Vietnam War. That might not have been right or fair, but the fact that the top commanders in Vietnam, starting with Gen. William Westmoreland, had all fought in WWII led to an unfortunate conflation of the Good War and the Vietnam quagmire.

In 1971, NBC Nightly News anchor John Chancellor said simply on his broadcast, “Today is the sixth of June, D-Day,” and left it at that. That same year, the TV sitcom All in the Family made its debut. The comic anti-hero character, Archie Bunker, was held to be a WWII vet with an undistinguished record. To liberal comedy writers, that was a good hook for a joke or two.

This photograph from the National Archives taken on June 6, 1944, shows U.S. Army troops wading ashore at Omaha Beach in north-western France, during the D-Day invasion. (Robert F. Sargent / STF / NATIONAL ARCHIVES / AFP /Getty Images)

Then in the 1980s, WWII started to look better. The hinge came with President Ronald Reagan’s trip to Normandy in June 1984, there to pay his respects to the dead and to deliver his marvelous ode to the Boys of Point du Hoc.

That same year, another NBC News anchor, Tom Brokaw, visited Normandy. Contemplating what his own father, and so many soldier, had gone through in the fighting, “I underwent a life-changing experience.” So he went to work. In 1998, Brokaw published his compendium of memories from WWII, The Greatest Generation. That same year, Saving Private Ryan.

By now World War II nostalgia was in full swing—and has grown stronger with passing years, including big-budget epics such as Band of Brothers, The Pacific, and Masters of the Air. Today, some three million tourists come to Normandy each year, mostly to gaze on Gold, Juno, Sword, Utah, and, of course, most poignantly, Omaha.

Still, it’s bittersweet to think, as the historian Turner would have predicted, that memories of D-Day have improved, even as the heroes themselves have mostly disappeared.

In fact, as the old soldiers fade away, one thinks of the words of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who fought in France in WWI and then, in WWII, led American forces in the South Pacific. In 1962, when he was in his 80s, with not long to live, he spoke at West Point:

The shadows are lengthening for me. The twilight is here. My days of old have vanished…They have gone glimmering through the dreams of things that were. Their memory is one of wondrous beauty, watered by tears and coaxed and caressed by the smiles of yesterday. I listen then, but with thirsty ear, for the witching melody of faint bugles blowing reveille, of far drums beating the long roll. In my dreams I hear again the crash of guns, the rattle of musketry, the strange, mournful mutter of the battlefield.

We should all be that poetic, as well as heroic. And then MacArthur added, “Always there echoes and re-echoes: Duty, Honor, Country.”

Yet amidst all the warm emotion of D-Day, it’s hard not to notice that on the home front, political passions are hot and getting hotter. Here, the word is polarization, not commemoration.

What will happen to these United States in 2024? And in the tumultuous years that are certain to come? We can’t know.

Yet we can all sense this much: If there is to be a national reconciliation, it will be on the basis of our shared kinship to the hallowed heroes of D-Day and all their comrades. They fought and died for us, and so now, it’s our duty to keep faith with them, harkening to their ghostly whisper: Duty, Honor, Country.

The patriots today who accept this responsibility will be the rocks upon which our civic faith is renewed and restored.

This article was originally published by Breitbart. We only curate news from sources that align with the core values of our intended conservative audience. If you like the news you read here we encourage you to utilize the original sources for even more great news and opinions you can trust!

Comments